An Excerpt From Ruth Jean’s New Book

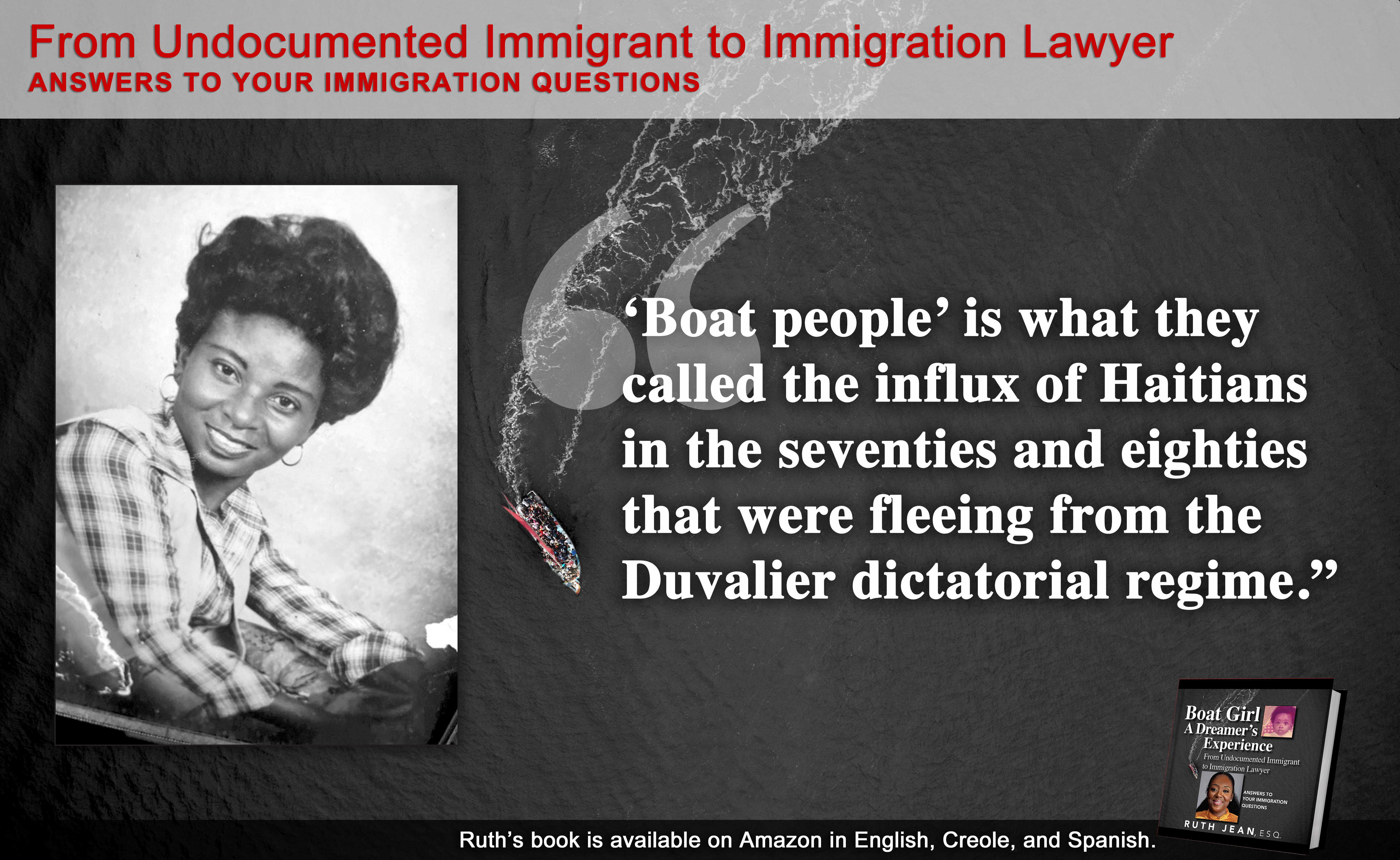

My mom became my hero that day, and for her sacrifice I am forever grateful. I don’t have any memory of the day my mother decided to travel by boat with us, but I know that without this revolutionary decision, I would not be where I am today.

I can vividly envision the scene based upon what my mother told me—the way I was standing on one side of her with her arm around me, my middle brother standing in between my mom’s legs as she held my newborn baby brother tightly in the one arm that was not around me. I can imagine the small boat out there in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean filled with people who were hopeful yet desperate for another life. I can imagine the mixed feelings of those wondering if they’d survive this trip and planning what they’d do the rest of their lives if they did survive.

Some planned to go to school to better themselves; some planned to find a job to help their families back home; some planned to help their children go to school; some sought the ability to speak freely and practice their lifestyles without threat from the government.

Mom says that we ended up somewhere on the Keys, Key Biscayne probably. When we landed, we were rescued by what Mom thought was Immigration. They gave us food, warm clothes, and the opportunity to make a phone call. Mom called a family member, and we began our lives in the US.

To say we struggled would be an understatement. I often say to others that I came from humble beginnings. Well, that’s just a euphemism for poor. We were poor. My mother was raising us on her own as a single mother and we were in culture shock. When I was about six, we moved to New Jersey. I don’t remember much of anything before I turned six, and I believe it’s because of trauma that I experienced during those years. My mother did all kinds of jobs expected of an immigrant—she cooked, cleaned, and picked fruits and vegetables. When my father told her he wanted us to move to New Jersey, she was more than happy and welcomed the help he could provide with raising three children.

When we lived in New Jersey, we lived in my aunt’s basement, but it was stable. We had some stability. I had no idea that we were “undocumented.” I went to school just like the other children, and my parents went to work just like the other parents. We spent about three years in New Jersey until we moved down to Florida. We moved into the middle of the “hood”—the inner city. While where we lived was majority Black and everyone looked like us in terms of skin color, we stood out and were not always welcomed.

Haitians dressed their children differently, wore different colors, spoke with a different accent, cooked foods that smelled different, and combed their daughters’ hair differently.

Even though I had no accent, it was obvious that my parents were not American. This was culture shock. When we played outside with the other kids, there always came a time when the parents would begin calling their children to come inside. Everyone knew me as Ruth, but when my mom would shrill out in her high- pitched voice, she’d yell “Wheat! Wheat!” (which is how my name sounds to a non-creole-speaking individual). So, of course, the American kids made fun of how my mom called my name.

Being Haitian was hard, but being undocumented and Haitian was even harder because you couldn’t catch a break. Americans didn’t like you because youwere Haitian and Haitians who were “legal” looked down on you because you came to the United States by boat.

To Be Continued...

Can’t wait? Her book is available on Amazon in English, Creole, and Spanish. BUY NOW